If an interviewer were to ask Lebron James how he expected to perform before a game, he wouldn’t hedge and say, “We’re probably going to lose” just to impress everyone if they happen to win. With his career average of 27 points per game, he would be unlikely to say “I hope to score at least 6-8 points tonight.” It sounds ridiculous, but this is exactly how corporate managers have been conditioned to prepare and submit plans, budgets, and forecasts.

The technical budget development term is “sandbagging,” whereby one deliberately understates expectations to improve the perception of their subsequent performance. You know it well and have seen it many times—though doubtless by others (you would never engage in such unpleasant practices yourself). But despite recognizing the underlying problem, most managements allow it to persist. To break these bad habits, companies should delink performance targets from plans and budgets.

Once the head of a business unit or functional department understands that their plan is effectively a benchmark for success, this affects their motivation to aim high. Given whatever level of performance a manager actually achieves at the end of the year, a “stretched” goal makes management’s performance appear worse, so they earn less. If managers seek to earn more, and most do, they have an incentive to plan for mediocrity.

It takes discipline to build long-term value, but it also requires creative thinking about what’s possible. The following is a prescription for setting aspirational goals by breaking managements’ reliance on budgets as performance targets—all of which has been shown to yield stronger motivations to seek new and innovative ways to create value.

Thinking Big, Aiming High

When the New York Giants defeated the otherwise undefeated New England Patriots in Super Bowl XLII in 2008, they were the underdog in every round of the playoffs. They performed so improbably well that they knocked off heavyweight after heavyweight, eventually winning the championship. Few sports analysts believed that a Giant victory was even remotely possible, but as was obvious to everyone watching the game, the Giants had other ideas. They may not have been the best team in the NFL that year, but they were the best team on the field that day.

In business, we see similar upsets. Every year management teams are underestimated within their industry, but manage to achieve an outcome broadly viewed as impossible. The only difference is the experts are on CNBC and in The Wall Street Journal, not ESPN. So, what does it take to cause an upset in the industry in which you operate?

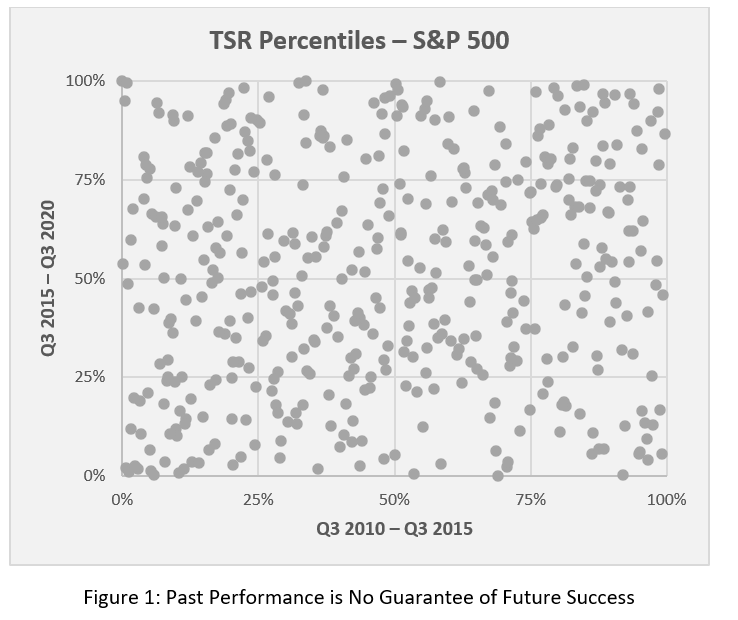

The same principles apply to industry leaders—how do you avoid an upset? What does it take to maintain a lead and avoid being Microsoft’s IBM? Or Google’s Yahoo or Ask Jeeves? The fact is, past performance is far less a predictor of future performance than many count on. The threat is real—during the five years ending in the third quarter of 2020, the companies that were top-quartile performers during the previous five years were slightly more likely to be bottom quartile than top quartile.

Few success stories, in sports or business, begin with a goal of mediocrity—yet that’s what most managers are paid to submit. We don’t want unrealistic plans; but from wherever we are, we want to stretch. This is how great companies consistently beat expectations and deliver “alpha,” or unexpected TSR.

Restoring the Purpose of Planning

Before explaining how to separate plans, forecasts, and budgets from the target-setting process, consider the benefits when planning processes can be relied on for actual planning. We no longer see mere incremental improvements here and there; instead we uncover game-changing strategic ideas—even if they upset the apple cart by cannibalizing what we already do. To prompt such aspirations and transcend the status quo, managements should stimulate the planning process by deploying “stretch” goals that are a bit uncomfortable. This tends to get managers to go beyond merely extrapolating what they’re already doing now.

In practice, calibrating the right level of difficulty is a bit of a balancing act. We want to expand managerial thinking and strive beyond what seems readily achievable; but we also must be careful not to set unrealistic goals, which can be as counterproductive as sandbagging.

Though it cannot always be calculated with precision, due to the inherent subjectivity involved, an aspirational goal should be within the realm of 20-40% achievability. The response of a management team to such a challenge should be: “Where in the world are we going to find such improvement?” Maybe they can take that research they did and use it to enhance the product and drive market share or pricing. Or maybe they can push into that new region they have been talking about to secure new customers and more sales. Or they might get off the dime and acquire that smaller competitor that has new products and brands, or is operating in a desirable, or untapped, region. Sure, there is risk in new products, new regions, and acquisitions, so we need to be careful to balance risk and return. But the conversation is taken much more seriously when managers have to find a way to close the gap to a stretch goal, than with sandbagged goals that are almost automatically achieved.

Aspirational goals can work as part of an annual budgeting process, but they are more effective as the start of a three- to-five-year planning process. The fact is, large strategic investments take time to devise, develop, execute, and then show up in results. Because of this, many common annual performance measures can send signals that conflict with optimal long-term value-adding decisions—which brings us to the importance of measuring improvement with the “right” performance measure.

A Reliable Benchmark for Value Creation

As discussed in Curing Corporate Short-Termism, common performance indicators like return on invested capital or EBITDA (or other rate of return, profitability, or growth metrics) are partial measures that often don’t relate particularly well to value creation.

In isolation, such measures are incomplete and can lead managers to make poor decisions, especially over the long term. But it is possible to combine aspects from these different measures to reliably capture and indicate value creation, or expected TSR. While the concept of economic profit has seen little fanfare since the downfall of Economic Value Added (EVA) in the late ‘90s, there is tremendous value in the concept of combining both key performance dimensions—return on capital and overall growth—into one overarching measure. As mentioned above, the most commonly recognized such measure is EVA. But since the measure is very complex and unwittingly discourages long-term investment, we don’t recommend that companies use it.

Fortuna Advisors’ Residual Cash Earnings, or RCE, metric was designed to be simpler than EVA and to track value creation better, without the bias against investment. RCE removes the effects of depreciation that cause EVA to make new growth investments seem expensive while old, depreciating assets look cheap. Our research has also demonstrated that changes in RCE relate better to changes in TSR than EVA and other common measures, so there is a robust linkage to value creation.

Once we have settled on a measure like RCE to gauge improvement, a reliable technique for setting aspirational goals is to derive them from the market. As suggested by the relationship between RCE and TSR, the net present value of RCE links back to corporate valuation. Normally we forecast financial performance, convert the forecast to RCE, and calculate the present value of RCE to determine the valuation of the forecasted performance. For goal setting, we do this process in reverse.

The expected RCE can be determined and linked to the drivers of revenue growth, margin, and other key variables to indicate a reasonable path to achieve investor expectations. Strategies and initiatives intended to change margins or asset intensity can be incorporated in general terms. If everything stays the same, we would expect that, if management achieves this forecast, the share price will grow at the cost of equity that is implied by the Required Return.

The first step is to determine the average future RCE improvement that is implied by the current valuation. Usually we start with either the RCE from the prior year or, if the current year is expected to be very different, the RCE implied by consensus forecasts for the current year. If we then make the simple assumption that RCE remains flat, it is easy to determine the valuation implied by this flat RCE. If this valuation is significantly higher or lower than the firm’s current market cap, then we need to adjust the RCE forecast to reflect a straight-line performance decline or improvement that equates the company’s implied value with its actual valuation in the market.

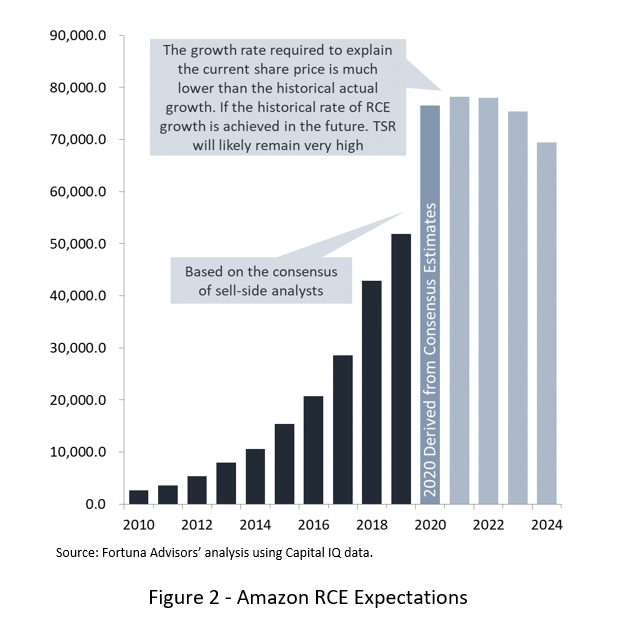

Consider, for example, the expectations for future RCE improvement for Amazon as of October 2020 shown in Figure 2. Using these numbers, we can then solve for a combination of growth, margin, and investment by year that exactly corresponds to the RCE trend and seems plausible versus current performance. Preparing such a forecast is a blend of science and art. If we assume too much growth, then margins may need to decline in a seemingly random way to achieve the RCE forecast. If we don’t assume enough investment, asset intensity may decline rapidly while reinvestment effectiveness skyrockets—both in ways that fail the smell test. When a combination of growth, margin, and investment is settled on that feels balanced and plausible, we refer to this as the “investor expectations” forecast.

For Amazon, the RCE growth rate required to achieve the “investor expectations” forecast is much lower than the actual historical growth rate. If the historical rate of RCE growth is achieved in the future, TSR will likely be very high, as it has been in the past.

Thus far, this analysis reflects investor expectations that will typically not reflect enough improvement to be considered a stretch goal. Sometimes, though, the performance already baked into a share price can seem like a stretch to management. In these cases, the stock price may be “too high.” Not many executives are comfortable thinking, or even worse saying, that their share price is too high. Logic tells us we should expect our price to be too high about as often as it is too low. But many executives don’t see it that way, which is why this analysis is so useful.

Target-Setting to Facilitate Aspirational Goals

Many companies set aspirational goals above what is embedded in the share price. A solid approach can be to strive for top-quartile TSR over, say, the next three years. Averaging the last 100 (overlapping) three-year cycles, rolling back monthly from October 2020, the 75th-percentile company in the S&P 500 delivered annualized TSR that was about 8.0% higher than the median company. This number could alternatively be derived from the Russell 1000 or an industry peer set. For example, the 75th-percentile consumer discretionary company delivered 9.3% more annual TSR than the median consumer discretionary company, but in utilities this gap was only 3.6%. It is no surprise that in some industries performance varies more, and it takes a greater level of outperformance to be top-quartile. Bear in mind, though, that generating an extra 3.6% TSR per year in a heavily price- and, often, rate of return-regulated utility environment may be a lot tougher than it seems.

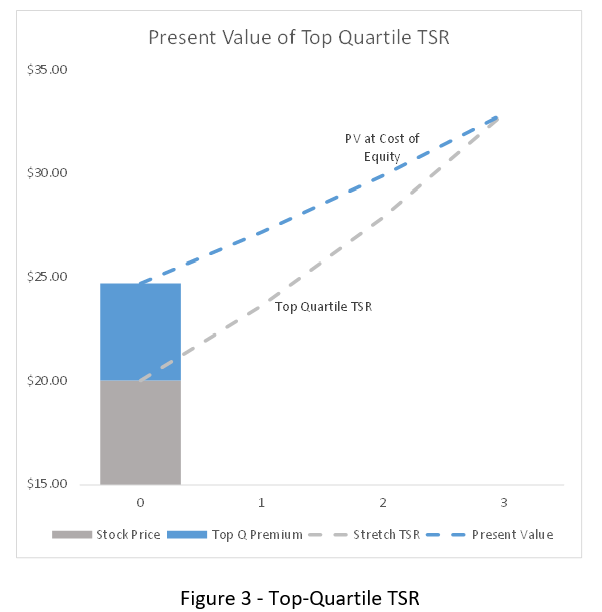

The process for setting aspirational goals starts by increasing the starting share price for the above analysis by growing it at the cost of equity plus a premium corresponding to the 75th percentile. Let’s use, say, 8% for our example. Then we discount it to the present at the cost of equity.

Consider a company with a $20 share price and a cost of equity of 10%. We would first grow the share price out three years at 18%—i.e. the 10% cost of equity plus the 8% premium required to be top-quartile on TSR. This gives us $32.86, which is the expected price three years from now if we achieve 18% share price performance. We would then discount this back to the present at 10% to get a value of $24.69. This would then be used in an analysis similar to the above investor expectations example to set aspirational goals for growth, margin, and the other key variables. This is a useful process because it sets a goal for how much investment and return are required to produce the RCE growth that is expected to be needed to be a top-quartile TSR company. If everything stays the same, we would expect that if management can achieve this forecast, the share price should grow at a level that is expected to be top-quartile, as shown in Figure 3.

This approach has the virtue of being objective and explainable. Not that we need to explain all the math, but it seems better to say “we analyzed the level of RCE improvement that we believe is needed for us to be a top-quartile stock,” as opposed to “we increased investor expectations by X because we said so.”

Companies with large and diverse portfolios should also consider allocating goals by business unit. To do so, business unit managements should build a plan to achieve some combination of the performance drivers that deliver their business goal. They may not always be able to get there, but gaps between the sum of these plans and the aspirational consolidated goal can potentially be filled through acquisitions.

The Bottom Line

Of, course, some businesses have a lot more, or a lot less, opportunity, and management can adjust the aspirational stretch goal to calibrate it to their sense of difficulty. But the process is useful in understanding what is needed over the long term to stimulate thinking beyond the status quo and exceed expectations. Embracing these practices and measurement frameworks, to replace plan- or budget-based performance targets, can establish powerful incentives for managers to seek unexpected sources of value creation.

Passages from this article are adapted from the author’s book, Curing Corporate Short-Termism

Greg Milano is founder and CEO of Fortuna Advisors.