© BRIANAJACKSON/ISTOCK/THINKSTOCK.JPG

It is fair to say that corporate filers have taken on a disproportionate part of the burden during the early, bumpy days of XBRL and the payoff is being realized much slower than had been promised. It’s not hard to see why many in corporate finance want to wash their hands of it.

Yet now there is clear evidence that XBRL is turning the corner. A significant number of financial information providers (including some large ones) have adopted XBRL as a part of their data gathering, allowing for faster and more detailed information to be passed on to their customers. In fact, we estimate that greater than 40 percent of investors are currently receiving the benefits of XBRL. Most investors do not even realize they are using XBRL based information because it is coming to them through a major financial data provider or website. More importantly, we expect that number to be near 100 percent in two years. Despite the many well publicized complications with XBRL, the richness and timeliness of this interactive data being created by America’s corporations is far too powerful to ignore.

The benefit of using XBRL based data goes well beyond investors. Many users of the data are the same companies who also create the information. XBRL based data is available at your fingertips, providing insights about competitors, suppliers, customers, or market trends. You can more easily than ever search for very granular information within a group of companies, and analyze a particular company’s information within a few minutes of their 10-Q or 10-K arriving at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. These are true innovations possible only because of XBRL. Once you become accustomed to them it is very difficult to imagine going back.

You can spend time talking about how the exemption for public companies with annual revenues under $250 million from filing using XBRL is an arbitrary measure, and far disconnected from the “small, emerging growth” label being tossed around by the bill’s sponsors. But in reality there is no correct measure, because any company large enough to be traded on a US exchange is big enough to file interactive data.

The main purpose of the adoption of XBRL and interactive data in a more general sense was to make financial accounting information more accessible and easy to use for investors and potential investors. Even before the adoption of XBRL, the largest companies were the ones that got more analyst coverage and were followed by most investors. The main reason for that was that more information existed for those companies rather than for the smaller companies.

Many data vendors provided information just for the largest companies and not for all public companies. One key benefit of the adoption of the Interactive Data regulation was to democratize the information and make information for all publicly traded companies cheaper and easier to access. Exempting smaller filers would worsen the situation by making information about the largest filers more accessible (thanks to the interactive data) while information about the smaller filers would become even harder to access.

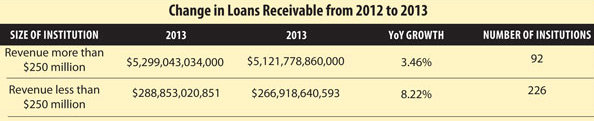

There are several examples of analyses that can easily be accomplished in a quick and timely manner thanks to XBRL based data. One example comes from the world of banking where you are able to analyze Loans Receivable across a broad range of lending institutions. The table here

shows that while loan book for the larger banks were dominant, regional banks have a higher percentage of loans made (8.22%) from 2012 to 2013. This is very good news for the macro picture, and without XBRL, it wouldn’t be available to the public as easily.

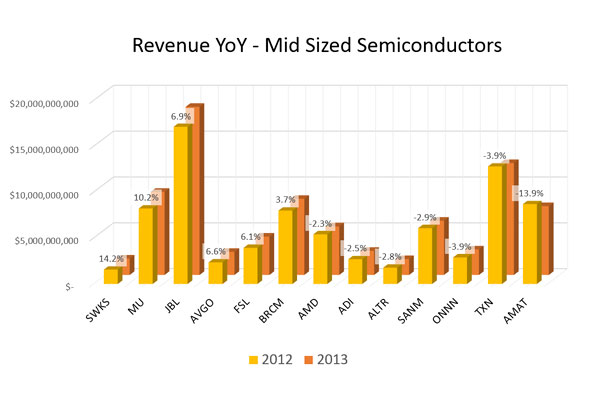

Another example is for simple industry analysis. In this case we are looking at mid-sized semiconductors. The 10-K season isn’t quite over yet. But enough companies have filed that you can get a good picture of what the economic picture is for 2013 as opposed to 2012. Here we examine semiconductor and related companies between $2 billion and 20 billion in assets. It is interesting to note from the chart the pretty balanced split between winners and losers.

Information coming out of similar analysis helps smaller firms as well.

For example, who hasn’t had a request like, “How much would it cost us to build a widgets business versus buy Widgets International, or North American Widgets?”

How would someone value Widgets International or North American Widgets today? Would they potentially miss Widgets.com, that had revenue of 150 Million last year, up from 45 million the prior year? Would the acquiring company rely solely on their bankers to give that information?

Any cost savings earned by not filing in XBRL will be dwarfed by the opportunity costs of not doing so in an interactive format. Digital financial reporting is long overdue, and moving back to a paper based system, even temporarily, is not the path forward. XBRL is driving true innovation in the financial sector and now is absolutely not the time to stop it. Instead we should be talking about how to make it better, easier to use, and eventually, how to expand it.

Pranav Ghai is the co-founder and CEO of Calcbench. Ariel Markelevich, Ph.D., CMA is an Associate Professor at the Sawyer School of Business in Suffolk University. He is also the Chief Product Development Officer at Calcbench. Alex Rapp is the co-founder and CTO of Calcbench.